In a little under ten years, Superman will go into the public domain—for all that that means in this day and age. The simple truth is that as long as a company with millions to burn in legal fees says something is off-limits, then it is.

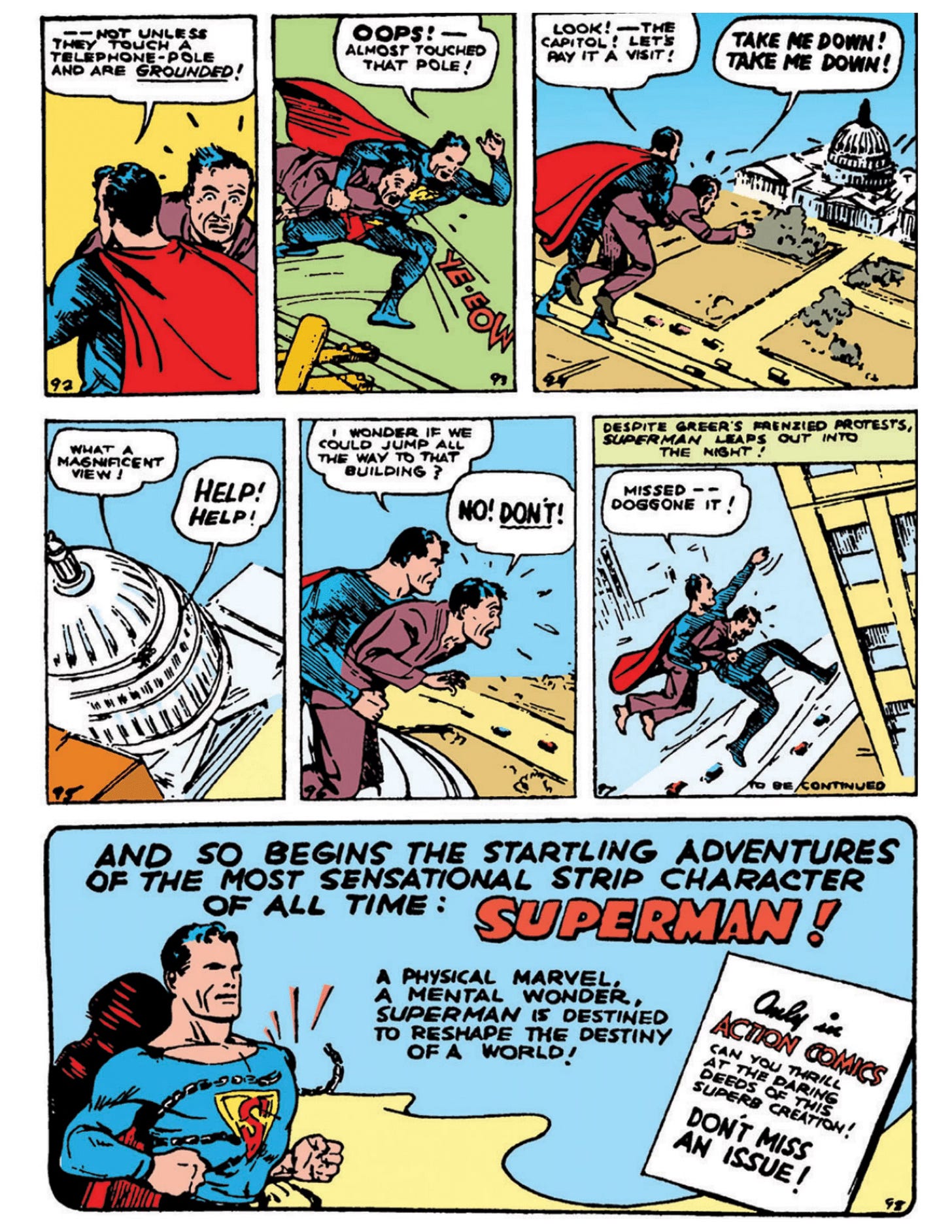

Regardless, if you’ve marked your calendar with the exact date that it's “legal” to publish your own derivative of Superman, keep this in mind: what will be available in 2034 won’t resemble Superman in any serious way—not the way we know him today. Most of you probably know that his powers were nowhere near as godlike when he started out. His abilities were much closer to the Gladiator character that his creators ripped off. Okay, a lot of writers like the idea of a nerfed Superman, but the bigger problem is his character. When Superman first showed up, he was kind of a thug if you want the truth.

Action Comics #1 reveals a Superman that is pretty far from the aspirational deliverer that leaps to mind when his John Williams theme plays. His enemies aren’t the forces of nature that are the only thing powerful enough to oppose the archangel-demigod from Kansas. His enemies are a wife-beater, a bullying gangster, a corrupt politician, and a corrupt system that nearly executes an innocent man.

When he was first introduced, Superman was breaking the wheel of fate that crushed the helpless beneath it. He was "opposing the order of life and the gods that proclaimed it so." He was, in short, a trickster hero.

Given the world he was born into, it’s not really a surprise. 1937 was a time of fear and insecurity. Men who had built houses with their own two hands had those houses stripped away when the twenties turned into the thirties and all the good jobs vanished. Farms in the West were swallowed by the Dust Bowl. The French had allowed the Rhineland to be remilitarized because they were afraid of Communist Russia. Trickster heroes are always popular when times are tough. Maybe you can’t destroy the system, but you can give it a black eye and laugh at it.

Superman appeared in a vacuum. While he was a product of plagiarism, he was the only one of his kind. The rest of the comic book industry revolved around exciting adventures in untamed parts of the world and detective stories in America. That changed quickly.

National (DC) Comics never disclosed its actual sales figures and they appear to have lost the records by the time anyone was interested in those sorts of numbers. Regardless, the sales had to have been in the millions. Superman erupted onto the scene in a pop culture seismic event.

Supermania took off in 1939. The franchise was expanded accordingly. The McClure Newspaper Syndicate started publishing reruns of Superman in the comic strip section of their papers. Up until then, comic books were just albums for collected back issues of comic strips. It wasn’t supposed to work this way, but Superman made it happen.

Every comic book publisher in the country ordered its wage slaves to start pitching them new ideas for “costumed crusaders,” “mystery men,” and “masked avengers.” The term “superhero” wouldn’t be invented for a while. Some, like The Red Bee and Fantom of the Fair, failed. Others found a footing. National’s Adventure Comics title turned into an audition space for new costumed crusaders: Hourman, Starman, and Sandman. They did all right at first but eventually faded away. Blue Beetle was a complete failure at first, but the concept kept getting reworked.

National struck gold again the next year when Detective Comics #27 featured a masked avenger with a bat fetish.

In 1940, the dam burst and hundreds of superheroes flooded the newsstands. Nobody is quite certain how many there were—in part because the definition was fairly elastic back then. For instance, Zorro and The Shadow meet all of the qualifications to be a superhero, but they are never counted in their number.

1940 was also the year that Superman became a radio star when The Adventures of Superman hit the airwaves, with Bud Collyer starring as the first incarnation of Kal-El of Krypton. It was also the year that Wonder Woman debuted and the first superhero team—the Justice Society—gathered. National’s rivals moved in hard, trying to take away as much of their market share as possible.

The Golden Age of comic books had begun.

Masked avengers were all pretty big on fighting corruption in those early days. It was understandable when you think about it. The entire system had failed the common man, yet there were still people becoming stupendously wealthy—even in the deepest days of the Depression. And while the causes of the Depression were more complicated than just greedy politicians and bankers, there was some truth to it. Teapot Dome was still a pretty fresh memory.

Then there was the simple matter of affordably cheap escapism, which comic books provided in abundance—enough so that it began to devour pulp fiction’s market share. Its most reliable demographic, the young male reader, defected in droves to this medium. Comic books offered visual immediacy in a way that books just plain couldn’t. And the old saw about how comic books were for illiterate mouth breathers wasn’t entirely inaccurate. The more, shall we say, reluctant reader found comic books more approachable—especially younger readers. Seven- and eight-year-olds had no difficulty keeping up with the plots.

All of these factors had the pulp publishers declaring war on comic books. They had been reluctant at first because copyright laws were pretty vague on this new medium. Arguably, just providing pictures made them legally distinct enough to avoid infringement. (This argument failed, by the way.) By 1940, survival was at stake.

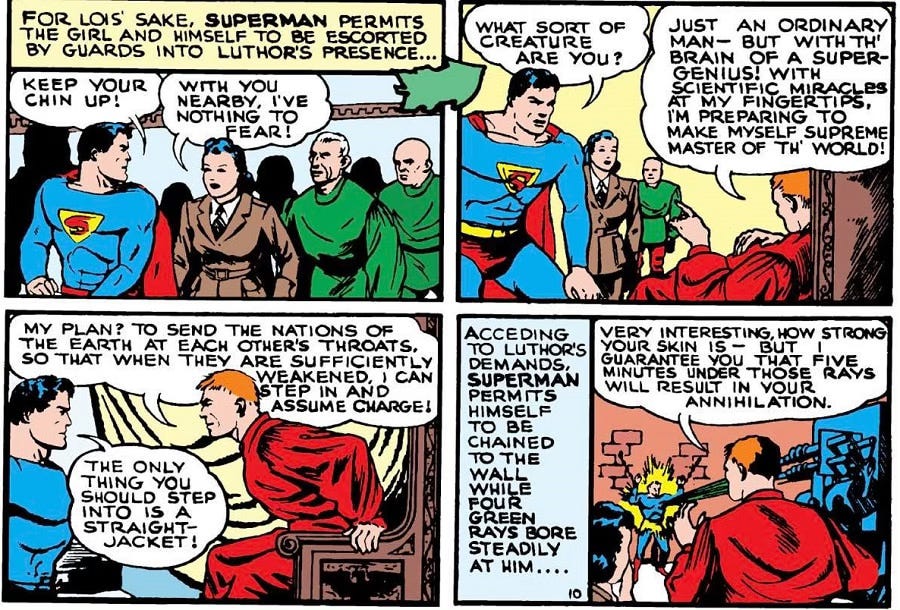

I’ve already covered just how much of Superman was stolen from the various pulp franchises. At this point, Superman’s editors—at the urging of National Comics’ legal team—began to significantly redirect the Man of Tomorrow’s efforts. In March 1940, Lex Luthor made his first appearance.

This marked a big shift for Superman: away from fighting corruption and toward battling megalomania.

The reason was obvious. War had descended on Europe once again. Americans didn’t particularly want to be involved, but they hadn’t been all that keen on joining the Great War either—and it still happened. Hitler’s constant saber-rattling made him easy to paint as a villain. The invasion of Poland left no doubt as to who the aggressor was. Then came the Fall of France.

France—that hadn’t been crushed in centuries. France—that had held out for years in the bloodiest war in human history and that Americans had fought to defend twenty years before. France fell in just 40 days. It was an earthquake.

Superman and the rest of the superheroes were frequently foiling plots built around cruel German inventions. The comic books' hostility toward Germany was becoming palpable.

Part of this was that the publishing industry was headquartered in New York City, and the Big Apple has always had a sizable Jewish population. Hitler’s ethnic cleansing hadn’t begun in earnest yet, but it was already known that Jews in Germany were getting it much worse than they had in Imperial Russia.

Superman’s creators were both Jews, which I believe affected his development. First, there is the obvious Moses parallel—although having him found by a dirt farmer and his wife instead of wealthy elites was a nicely American touch. But this does raise Superman’s status as a perpetual outsider. He loves America and all things American, but in the final analysis, he doesn’t truly feel like he’s one of us. He knows he’s an eternal alien with no home to back to. Always just a bit isolated.

By the middle of 1941, superhero stories were already taking on a more militant tone. While Superman and Batman never outright joined the armed forces, their stories became filled with saboteurs, fifth columnists, and mad scientists in suspiciously German-looking uniforms. The comics were laying rhetorical groundwork for war before Roosevelt ever addressed Congress. Superheroes weren’t yet soldiers—but they were already soldiers of fortune, of justice, of propaganda.

And then came December 7th. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor would transform the American psyche—and with it, the nature of its myths. Overnight, the dream of the powerful man who could leap tall buildings became something else entirely: a call to arms, a fantasy of righteous vengeance, a symbol of what America believed itself to be when its back was to the wall. Superman would no longer just lift cars or dangle racketeers off rooftops—he would represent a nation at war. The Golden Age had crossed a threshold.

In summary:

The Golden Age of Superheroes didn’t begin with a sense of triumph—it was born out of desperation, anger, and a need for control in a world spiraling toward chaos. Superman may have been crafted from borrowed parts, but he became something uniquely American: a folk hero dressed in circus colors who made injustice feel like it could be punched out with one clean hit. These early caped crusaders were brash, political, and only loosely bound by moral niceties. They weren’t gods yet—but they were becoming icons.

In the next chapter of this story, the masks come off, the gloves come on, and the superheroes go to war.

Discuss in the comments below

Might want to consider getting your history of comics into at least e-book form.

Good stuff.

We've got Gladiator and the circus tights, did he start with the trademark 'S' inside the diamond shield?