Chuck Dixon’s Cobra – A Study in Asymmetric Warfare (Part II)

The 1980s were the twilight of the classic American toy industry. Star Wars, Transformers, He-Man, Thundercats, and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Together raked in about $12 billion dollars and this was in real dollars, not the kind we have today (call it $33 billion in modern money).

The ad regulations I mentioned in the last piece were removed by the Reagan administration and allowed toy makers to directly advertise to kids using fully animated commercials.

And GI Joe was the Eighties apex of this tsunami of plastic. He-Man came close but didn’t knock the Joes off the top of their mountain fortress.

Hasbro followed the razor and blades strategy (or Barbie and her Dreamhouse if you like), the action figures themselves (Duke, Snake Eyes, Cobra Commander, Storm Shadow, and Destro were sold at little more than cost. The accessories were where your Dad, or more likely you (paper routes still a thing), started paying through the nose. HISS tanks and Wolverines would battle it out at the entry level. Skystrikers and Cobra Rattlers would dogfight at the mid-tier price point, and if you were rich, spoiled, and had literally every piece of GI Joe gear but no place to put it, your Christmas wishlist only had one legendary item on it: the USS Flag. An aircraft carrier/display case that was going to need its own room.

However, all of these toys were dependent on something. An active imagination. And Generation X was the last crop of kids that would need one of those in order to play.

While you certainly needed an active imagination for early video games, by the 1990s, that was becoming an optional extra. There was also the problem of market saturation. By 1988, Hasbro was clearly running out of ideas; that was when you started seeing figures like Cobra’s alligator trainer and Hardball, whose thing was being a baseball player with a grenade launcher. By the end of the decade, kids had a mountain of plastic spilling out of the toy chest. All of these things were leading to a market collapse.

Finally, there was plain old generational shift. Gen X started out growing their hyper-masculine toys, and the new generation preferred the Power Rangers.

On top of all of this was a major cultural shift. The zeitgeist that drove the GI Joe line of the 1980s was the product of the defeat in Vietnam and an escalation of tensions with a Soviet Union that was growing bellicose in its senility. But then came the lopsided victory of the Gulf War and the fall of the Eastern Bloc. The world that created America’s Highly Trained Special Mission Force was gone in a heartbeat.

There followed a decade in the wilderness where the United States found itself the sole superpower. A military designed for high-intensity, short-duration warfare found itself playing the world’s fireman, putting out dozens of little brush fires around the planet from Haiti to Somalia to East Timor. Chasing off mountain bandits who would be right back as soon as we left, and digging wells that we knew would fail in a year. We couldn’t fix their problems, but we could occasionally give them a single night with full bellies, no thirst, and no fear. What did that mean in the big picture? You’d have to ask God because we didn’t know. Hopefully, it meant something.

Then, in 2001, a new enemy emerged from the shadows to strike at America’s largest city to kill thousands.

The military adjusted to this emergent threat reasonably well. However, it took a while before the GWAT had fictional tropes and stereotypes that had stabilized in pop culture. It took a few years before regular people had a feel for this new war.

In the late 2000s, Hasbro had a GI Joe movie in serious development. They did not renew their contract with Devil’s Due Publishing and handed the license to IDW, which was making great strides in getting their graphic novels into book stores, which Hasbro was very interested in.

Cobra was updated as a modern insurgency with both overt and covert branches and a dispersed asymmetrical network.

Chuck Dixon, hot off Punisher War Journal, was a natural fit for this harder, grittier reboot. He wrote a G.I. Joe series that was about as far from the world of the 80s as the 80s were from WW II. The names were there, and shadows of characters you recognized. But this wasn’t about the Joes blasting HISS tanks that were rolling down Main Street. It was about hit-and-run attacks in the morally grey world of counter-insurgency.

1. Cell-Based Network

Dixon abandoned the idea of Cobra as a single, top-down cartoon villain army.

Instead, he depicted Cobra as distributed cells — small, semi-autonomous units spread across regions.

Each cell had its own leader, financing streams, and recruitment strategies, but all pledged loyalty to Cobra Commander as the ideological center.

This mirrored how post-9/11 terror groups like al-Qaeda franchised themselves — hard to kill because they weren’t centralized. If you killed a leader. Boo-hoo, time to pick a new lightning rod.

2. Corporate & Political Fronts

Dixon retained Hama’s Extensive Enterprises (run by Tomax and Xamot) but sharpened its function as Cobra’s lobbying and PR wing.

Dixon leaned into the idea that Cobra operated above ground through legitimate businesses, charities, and civic organizations, while using them as cover for insurgent financing.

This gave Cobra plausible deniability and influence within politics, echoing how cartels or insurgent groups legitimize themselves.

3. Military Arm

Dixon still made use of the iconic branches — Vipers, Crimson Guard, specialized units — but he reframed them as professionalized militias rather than toy-centric one-offs.

Elite groups like the Crimson Guard doubled as deep-cover operatives in civilian society.

Rather than huge cartoon battles, Dixon’s Cobra used these forces for precision strikes, ambushes, and propaganda victories.

4. Propaganda & Recruitment

Cobra Commander was recast as a charismatic insurgent leader who built the movement through messaging — anti-corporate, anti-government rhetoric, empowerment of the downtrodden.

Propaganda was critically important in bringing pressure against G.I. Joe as they were at best limited in their ability to counter program with their own propaganda.

Dixon emphasized the psychological war: Cobra didn’t need to beat G.I. Joe in open combat; it just needed to erode faith in existing governments and recruit the disillusioned.

In short, Cobra didn’t need to win. Only to survive.

5. Resilience Through Ideology

In Dixon’s version, Cobra wasn’t just a cult of personality around its Commander. It was an ideological insurgency designed to outlast leadership changes.

When Cobra Commander or a major figure like Chimera was killed or captured, the cells and ideology persisted.

This was Dixon’s key innovation: Cobra could survive decapitation strikes, just like real world asymmetric movements.

6. Hybrid State Model

Over time, Dixon also played with the idea of Cobra achieving quasi-state recognition (building on Hama’s Cobra Island precedent).

But he treated it less as a Bond-villain sovereign state and more as a terror statelet — comparable to Hezbollah holding parliamentary seats or ISIS seizing and holding territory.

✅ In short: Dixon organized Cobra less like Hydra or a Saturday morning “super-villain army,” and more like a cross between al-Qaeda, the Medellín Cartel, and Hezbollah — distributed, networked, resilient, and frighteningly plausible.

Dixon’s Cobra Story Arcs

The Joes and Cobra fought their war in the liminal land of low-intensity warfare, where frontal assaults are all but unheard of and progress was measured in inches gleaned through miles of secret trails in the night. A place where Judas is on the face of every friend, explosions of violence come between sips of coffee, and trying to find ways to convince yourself you are still the good guy gets harder with each mission.

It’s also a place where the unsung heroes in analysis became critical.

The first story arc followed an electronic counter-intelligence fobbit - “Mainframe,” who couldn’t convince the commanding general that Cobra was even real. He ended up going UA to try and find evidence to prove this existential threat actually existed. He spent half his time running from Cobra and the other half running from G.I. Joe.

In this shadow war, first-rate forensic accountants were more valuable than first chair shooters.

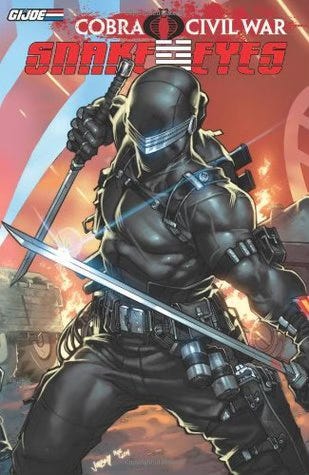

Pictured: G.I. Joe’s forensic accountant

The famous story arc was Cobra Civil War. A Joe had managed to assassinate Cobra Commander… And it didn’t mean shit. The only thing that happened was that that Cobra escalated their attacks as part of a process to select a new Cobra Commander.

Chuck Dixon didn’t treat Cobra as a cartoon army for Saturday mornings. He treated them as a warfighting entity that was frighteningly plausible in the post-9/11 world. The tone of his G.I. Joe comics was less “HISS tank rolling up Main Street” and more “Green Berets in the mountains.” Dixon pushed the Joes and Cobra into the liminal space of low-intensity warfare — a dozen hidden battlefields fought in alleys, deserts, jungles, and cities, with no clear frontlines.

1. The Cell Wars (Red on Red firefights)

Dixon introduced the idea that Cobra’s regional cells were so independent that they frequently fought with each other as much as with the Joes. These feuds forced the Joe team into the role of clandestine peacekeepers — keeping Cobra too divided to consolidate while trying to track down which cell was planning the next bombing or assassination.

2. Chimera’s Ascendancy

A standout creation of Dixon’s was Chimera, a former Green Barret psychiatrist who embodied the ideology of Cobra as a post-Cold War insurgency. Chimera was not a field marshal but a political warlord: building networks, recruiting the disaffected, and turning Cobra’s propaganda into a quasi-religious movement. He demonstrated Cobra’s resilience — even when Cobra Commander was absent or defeated, new leaders would emerge to keep the war going.

3. The Crimson Guard in the Shadows

Dixon doubled down on the Crimson Guard concept, portraying them not as ceremonial red-coated elites but as Cobra’s deep-cover infiltrators. Entire neighborhoods could be seeded with Guardsmen living average suburban lives, concentrating on their 9-to-5 jobs — bankers, teachers, city planners — waiting for activation when they would become something else. This allowed Cobra to wage psychological and political war from within Western institutions, echoing real-world fears of sleeper cells.

4. The Dirty Wars

One of Dixon’s recurring motifs was the moral erosion of the Joes themselves. Fighting Cobra meant dealing in assassinations, disinformation, and alliances with unsavory third parties. Dixon’s Joes weren’t just soldiers — they were spies, counter-terror specialists, and sometimes reluctant executioners. The line between “good guys” and “bad guys” blurred, as Dixon asked: What happens to heroes when they spend too long gazing into the abyss?

5. The Failed State Gambit

Expanding on Larry Hama’s Cobra Island, Dixon imagined Cobra trying to gain quasi-legitimacy in failed states. Cobra would install puppet regimes, buy up local industries, and sponsor militias in exchange for limited services. These storylines gave the war a global chessboard quality — not unlike how Hezbollah or ISIS created territorial footholds in unstable regions.

6. Information War

Dixon also understood that modern war is fought in the media. His Cobra used propaganda, disinformation, and cyber-attacks as often as bullets and bombs. The enemy wasn’t always visible — sometimes it was a whisper campaign eroding trust in governments, or a news report blaming the Joes for civilian casualties after a Cobra ambush.

The Underworld Battlefield

Dixon’s G.I. Joe was about a war fought in the margins of the map. This battle space wasn’t an aircraft carrier playset, but the gray zones of modern geopolitics: smugglers’ routes, failed states, rogue corporations, and infiltrated institutions. Victories were measured in scraps of intelligence pulled from a rendition interrogation chamber or in a Cobra harddrive exposing one of their fronts.

In Dixon’s telling, the Joes were not action figures — they were shades. They moved in the night, hunted men who believed themselves untouchable, and wrestled with the nagging doubt that maybe they were only holding back the tide, not turning it. Cobra could not be destroyed. It could only be fought, contained, and God willing - outlasted.

👉 That’s where Dixon’s run sits in the larger history of G.I. Joe: he made Cobra into something uncomfortably real. Not cartoon villains, not Bond-movie despots — but a reflection of the asymmetric wars America was fighting in the real world.

🧭 Conclusion: War in the Shadows

Chuck Dixon weaponized Cobra for the modern world. Where Larry Hama gave us a Cold War cartoon empire with a Bond villain at the top, Dixon built a networked insurgency that could give real intelligence analysts stomach ulcers. He understood that the battlefield had moved from aircraft carriers and arctic bases to back alleys, server farms, and boardrooms. Cobra under Dixon wasn’t some over-the-top Saturday morning punching bag; it was a living, highly adaptive threat that couldn’t be bombed into submission because it didn’t live in one place. It festered between the cracks of civilization itself.

.

Legacy and Relevance

In hindsight, Dixon’s run stands as one of the smartest evolutions of a legacy property in the post-9/11 era. While other franchises stumbled through awkward “dark ‘n’ gritty” reboots, Dixon simply treated Cobra the way real American strategists were forced to treat America’s new enemies: as ideological movements with long memories and flexible structures. He dragged G.I. Joe out of the toy aisle and into the real world of counter-insurgency, and in doing so, gave the property a true relevance it had never had before.

Hama gave us villains to defeat.

Dixon gave us an enemy to endure. And that’s why, years later, his vision of Cobra still lingers—uncomfortable, plausible, and disturbingly real.

Discuss in the Comments Below

Excellent article!

Did this actually make it into print?