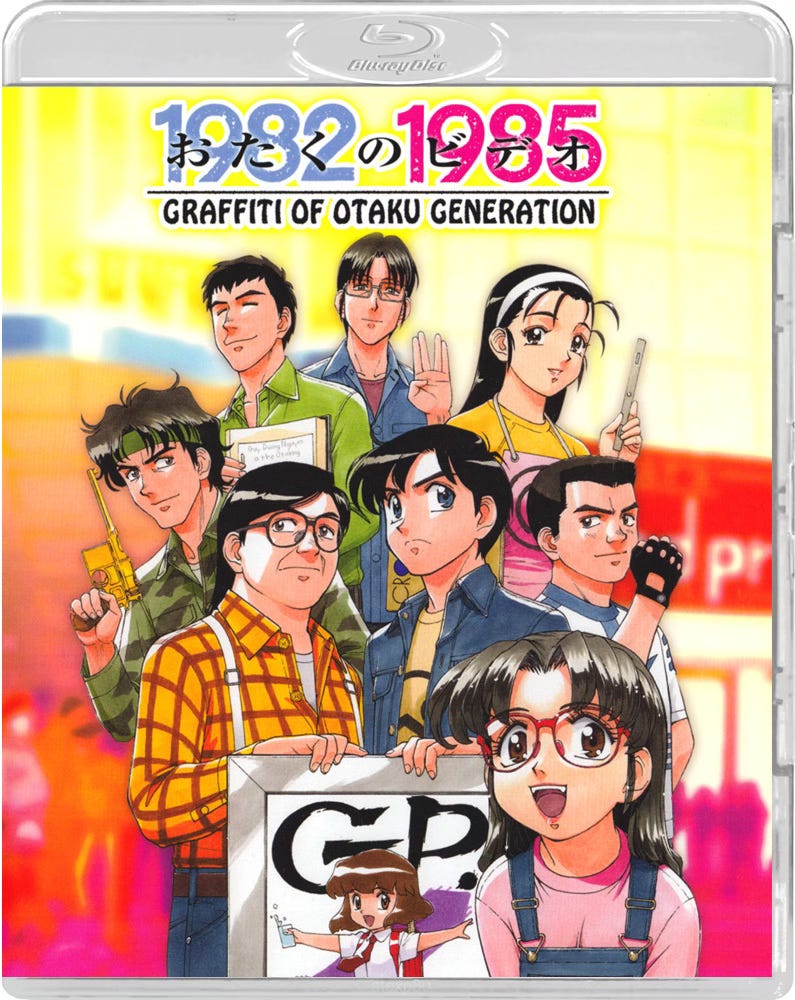

RE:Animation - Otaku No Video

This is the first of my retrospectives on the now sadly defunct anime studio Gainax.

Otaku No Video was by no means their first production and it certainly isn’t their most famous or most acclaimed or most successful but it is an excellent place to start this series because it was the project that was closest to their hearts as fans. And Fandom was what Gainax was all about.

It was a deeply personal project for them and I’m afraid one that proved rather prophetic in the end.

It was a mixed-media OAV, combining the animated journey of Ken Kubo into the darkest heart of fandom intercut with live-action mockumentary segments where all the actors’ faces are blurred “to protect their identities.”

And with the passing of decades, it’s taken on a third function - time capsule. It serves as a snapshot of what Japanese fandom and indeed fandom in general was like back in the 1980s. You can’t get across to kids today just how ostracized genre fans were forty years ago.

“You were better off walking down the street in chaps and a g-string than you were in a Starfleet uniform.” That is a fairly accurate assessment of what fandom felt like back then. You were totally outcast and you knew it. Grade school had sucked, high school had sucked a lot more, and college… didn’t. Not really, the rules were different once you were an adult but it felt like they were still the same.

There is an odd little flavor of narcissism to that. If you think the rules never apply to you, that is a classic sign of malignant (cluster B personality) narcissism, and thinking you will always be at the bottom of the social heap no matter what means you think the rules don’t apply to you. In a way, it made you super extra special. A secret king, as it were.

Regardless, in a world without social media, nerds and Otaku had to make do with each other’s company. Thus was born the geek watering hole called the science fiction convention. Which is where Gainax’s story properly begins.

Nihon SF Taikai ((Japan’s SF Convention), inventive I know), is Japan’s biggest con and takes place in various cities every year, each one however is more popularly known by the nickname related to the city it takes place in. Tokyo-TOKON, Nagoya-MEICON, Yokohama-HINCON, you get the idea. They are invariably organized by the local university students. Osaka’s is DAICON and it was at DAICON III (1981) that the Osaka University Animation Studies group (Anime Club) decided to create an animated short for the opening ceremonies.

None of them really knew what they were doing but they had a Super8 camera and a rough idea of how animation was supposed to work, and there was at the time a genuine amateur anime hobby industry in Japan.

They cut corners wherever possible using materials that were NEVER designed for animation. The short was rather ambitious for the talent pool that was available to it. Granted, they all became fairly well-known within the industry later. It had a theme if not much of a story. The Ultraman Science Patrolship lands and hands a girl in a student uniform a glass of water. The child and the water represented opportunity. She then faces a prolonged road of trials where every sci-fi IP in existence back in 1981 to include the Galactic Empire and the Enterprise tried to stop her, representing the forces that wanted to rob the young of opportunity. These bleeding-edge Gen-Xers knew something was up. She reaches her goal and uses her glass to water a withered daikon radish that immediately turns into a powerful starship that she takes command of and flies off into the star infinite.

This made quite a splash and there were quite a few anime professionals at DAICON III that were impressed with the amateur labor of love. Osamu Tezuka was rather hurt that none of his characters were used. This was corrected at DAICON IV (1983).

While the production had been difficult, the Osaka college students loved the final result and decided to take things to the next level. The DAICON IV opening was a genuinely professional-level production. Anime pros had introduced the kids around the industry, they had learned quite a bit and the DAICON IV opening had been shot at a dedicated studio. They had gone into six-figure debt to make this second film.

It’s still very much worth a watch (skip to the 2:00 mark).

To retire the debt, they sold VHS and Super8 reels (yes, that was a thing back then) of the DAICON III and IV at Comiket and other manga markets. As far as anyone can tell, this was the very first OAV. It was also completely illegal as they had not cleared the rights to any of the IPs they’d used. It was the first time they had done something legally janky but it wouldn’t be their last. I’m afraid it became part of Gainax’s corporate culture.

After the legally questionable sales, the studio founders had enough money that they decided to go legit and started production on their own IP, The Wings of Honneamise, (a beautifully animated film that I will cover later). While Wings was rightfully acclaimed it was not a money maker.

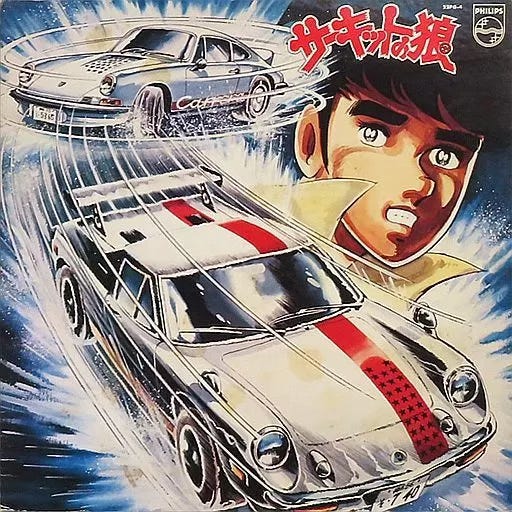

Consequently, Gainax decided to go back to making OAVs as the direct market was beginning to prove rather popular by early 1990. They adapted a number of mangas like Circuit Wolf

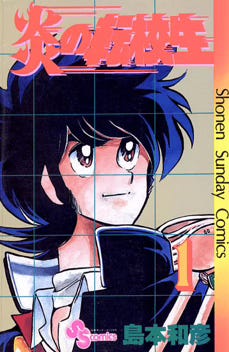

and Tenkosei,

Plus one of their own IPs (Gunbuster), these were a lot much more successful. That gave them space for a passion project. Which brings us to Otaku No Video.

The protagonist is Kubo a good-looking college freshman who is really into tennis. His friends are what were called Yuppies back then. They are interested in societally accepted status markers, the most fashionable labels to wear and the best cars to be seen driving, that kind of thing. He’s calling it an early night with his friends and is headed home when a herd of Otaku invade his elevator and start acting like nerds in public (where people can see them and everything). Kubo’s brief sideways glance says it all, he’s so embarrassed for them it is actually causing him pain.

But then one of them recognizes him. Tanaka who looks like a picture-perfect NEET to include glasses and thin suspenders with a belt. Kubo to his credit is actually glad to see his friend from high school and shows it. After this reunion comes the first of the Portrait of An Otaku cutscenes where live-action documentary interviews are conducted; an otaku discusses how his life has been ruined by being an otaku but still is one, clearly unable to break the cycle of addiction. The interviews are conducted and then “facts” about this degenerate lifestyle, which is how it is portrayed, are related afterward. Think Reefer Madness. They have never admitted it but it’s fairly obvious that the live-action otaku were Gainax’s founders: Anno Hideaki, Sadamoto Yoshiyuki, Yamaga Hiroyuki, Akai Takami, Takeda Yasuhiro, and Higuchi Shinji.

My favorite was the computer executive who admitted to being slightly interested in that stuff when he was a kid but was really into the more socially acceptable A/V club thing (how times have changed). The executive is then horrified when he is presented, Chris Hanson style, with proof that he is still part of this utterly debased lifestyle and is known to be “committing acts of cosplay.”

If you watch Otaku no Video you may be wondering why there were no gamers represented. I think this comes down to the personal prejudice of the producers. Even nerds have a hierarchy and that means someone has to be at the bottom of it. In the eighties, that was the gamers, even fantasy nerds looked down on them and that was saying something.

The animation picks up with Kubo at Tanaka’s place. Kubo was into anime for a while but left it behind when he went to college. Kubo now has a very large collection of videotapes. They take up most of his tiny apartment.

This is one of those time capsule moments. Gen Z has no idea how much space those old tapes they are so fascinated with took up. Nor how difficult it might be to find an obscure title. In the early 80s, this was due to the fact that American studios weren’t putting their A-list films on tape, which didn’t come close to stopping video pirates from making copies of them. But again, no internet, so video pirates had to network intensely. The same if you wanted a series that was never in reruns like Space 1999 or U.F.O.

Kubo is then introduced to the rest of Tanaka’s circle. Again, the time capsule effect is felt. There is the martial artist who has NEVER been in the ring, much less a real fight (another extinct form of Otaku, MMA killed them off). The military geek who was never in the military (they went mainstream with paintball, so again, they are no longer otaku). The hard sci-fi snob (a critically endangered species) and a cute cosplayer girl (bluntly a figure of myth back then).

As Kubo is sucked into the “lifestyle” he begins falling down the social ladder, eventually getting dumped by his otaku-hating girlfriend. The first half ends with Kubo declaring he will become the ultimate otaku, the Otaking.

The second half of the video chronicles Kubo and Tanaka’s rise as giants in the Garage Kit industry*, their fall when the money men took over during a cash crunch and then their rise again as an OAV production company, this part is definitely semi-autobiographical. Kubo eventually builds Otakuland and declares himself to be the Otaking. Then it jumps to 2035. Otakuland has long been flooded out due to global warming. Kubo and Tanaka, are now old men are exploring the remains in diving gear when the legally distinct Macross comes to life. They rush inside, and are now on the bridge of the Yamato. Kubo and Tanaka are young men again, they grab the throttle and launch into space.

A very Gainax way of ending an OAV series.

Japan’s Generation X was unique. By the time they were born the open wounds of the war had scarred over. They were the first genuine post war generation. They didn’t recoil at the military, they found the machinery hypnotic. They had the first genuinely prolonged adolescence in the country’s history. And the Otaku of that generation were far more influenced by pop culture than the classics of literature. For previous generations, Japan’s stylized memory of the Yamato was a way of coping with the loss of the war. For Generation X it was source material for a cool spaceship. Gainax was very much a product of Japan’s Gen X. For all the studio’s many faults (which I won’t shrink away from) they were the studio that was speaking from its heart.

Discuss in the comments below

*A brief fad back then. Most of the practitioners have long since migrated to Warhammer miniatures.

Hands off Anime Club makes so much more sense. TY for the backstory.

The nerd isolation from normality - the otaku-fication may be either a late 80s phenom as a result of pornification and an east coast thing.

In Cali at least the class prez and the sports captain and the D&Der and the kids making Our Star Blazers comic strip fan fiction all overlapped.

We had That One Guy, the fat kid gamma, but he was a bell-end.

At least they've already stamped their mark on history with Neon Genesis Evangelion.