In 1983 a writer (pen-)named Eiko Kadono was cleaning up around her house and noticed her daughter had been drawing some sketches of a Western-style witch. She was riding a proper witch’s broom and had a standard-issue black cat with her but was also listening to a radio. Eiko was intrigued by this. The dichotomy of the ancient and the ultra-modern has always been attractive to the Japanese. She sat down to write a story about this witch for her daughter, and very shortly Kiki was alive.

Kiki couldn’t make potions or cast spells or turn telemarketers into frogs. The only thing she could do was fly. She had to handle every problem like any other girl would. Kadono explicitly states in the introduction that she set out to explore the problems of adolescence in girls, and how they have to cope with their transition. All girls will eventually have to learn about love, become less dependent on their parents, and find something they are passionate about. The book is about a journey of self-discovery.

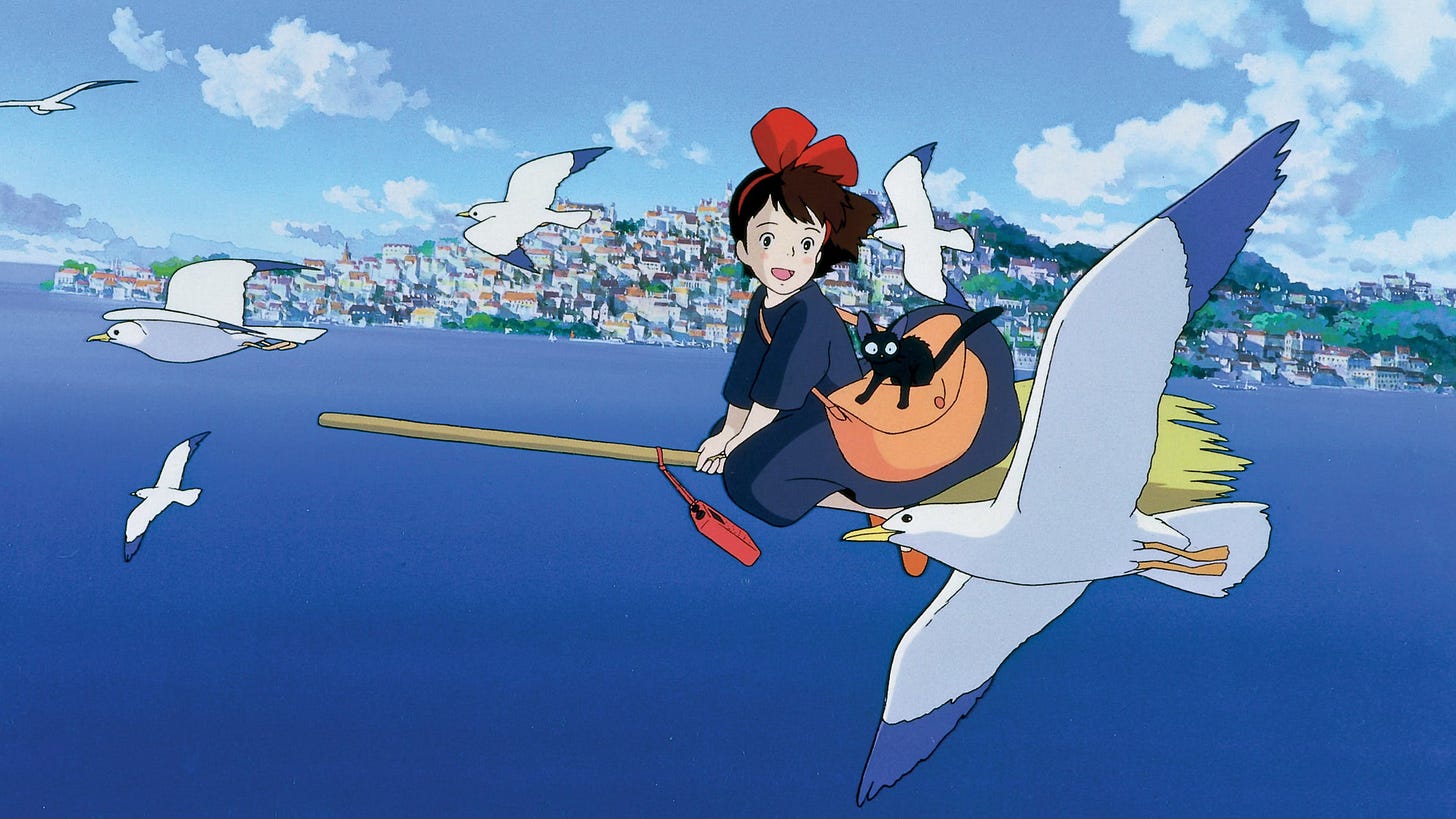

It was the start of a hugely successful children’s book series that rather irritatingly doesn’t have an official English translation. Four years after its publication, Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli began an adaptation of the work.

There are quite a few differences between the book and the movie. Some of these things are the result of moving from one medium to another. Others were deliberate creative choices by Miyazaki.

The film opens with Kiki laying on her back, watching the clouds go by listening to a 1950s-era transistor radio. She announces tonight’s the night, gets up, and starts running through the countryside. The architecture is distinctly European.

We meet Kiki’s mother who gives off Meg’s mother from a Wrinkle in Time vibes, she’s in her lab making potions and cooking dinner. Okay, she’s only making potions but it feels like she’s doing both. Anyway, we find out that it is the custom of witches to leave their homes at the age of thirteen years old, fly off to find a town that doesn’t have a witch and live there independently for a year.

We meet Kiki’s father who gives bumbling inventor energy, he’s a bit clumsy and Kiki repeatedly shows that she’s his daughter throughout the film.

Her mother is concerned that she isn’t ready but Kiki is determined and truthfully, kids are never really ready. Kiki is not wearing a black dress when we meet her. When she leaves she is wearing black indicating she has entered journeyman status as a witch. She doesn’t like the color. Modern parents are more than a little put off by the idea of a thirteen-year-old girl going off on their own but historically speaking for most of human history (and in some parts of the world today), it was the minimum age to get out the door and start getting after life.

Kiki takes off and most of her rural village shows up to give her a send-off. This tells you that she is genuinely well thought of in this small community. It tells you she’s thought of as a good person.

Kiki brings her black cat Jiji along who can apparently talk to her (we’ll circle back to the apparent part). Kiki meets a mean girl witch while she is flying. It gives you a preview of the problems she’ll face.

In the morning, Kiki arrives in a Mediterranean port city somewhere between Italy and France… And also between England and Germany, plus Scandinavia, the architecture is a little random. The name however is the distinctly Japanese “Koriko,” and has too many meanings to mean much of anything.

The town appears to be set in a Europe where there was never a First or Second World War. The technology is a little all over the place. There are electric ovens but the baker prefers to bake with wood fire. There are 1950s automobiles but there are also airships.

Kiki nearly gets arrested for disrupting traffic but is rescued when a boy named Tombo distracts the cop by shouting “Thief!” He introduces himself and she rejects him for being too forward.

Kiki is lost in this metropolis and is worried about having to go home as a complete failure. It feels like she can’t find a place for herself in Koriko. But then luck intervenes. A heavily pregnant woman comes out of a bakery and tries to flag down a woman pushing a baby carriage, who is just barely visible down the hillside. The distinctly maternal figure, (her name’s Osono), wants to return the baby’s pacifier but she is obviously in no condition to chase the woman down.

Kiki, who is happy to have an immediate goal, flies down to the woman and returns the infant’s pacifier. If an infant has a favorite pacifier this is no small favor. Kiki is rewarded and reports her success to Osono who takes her in for a coffee (hot chocolate in the Disney dub).

Japanese is a very contextual language. Depending on the Kanji used, Osono can mean counselor or advisor. And that is clearly her function here. This is where Kiki gets the idea of setting up her delivery service business. Osono is happy to let Kiki have a spare room if in exchange she is willing to help around her husband’s bakery.

What is really tragic about this, is that such an arrangement is probably illegal today. Certainly, the idea is rahter off-putting to Gen Z and Gen Alpha as something that just isn’t done. But it used to be fairly standard stuff. The bakery’s name in Japanese roughly translates to Rock Paper Scissors Bakery. This was a chance win for Kiki that could have easily gone another way.

Kiki sets off building her business, sometimes her clients are very good-hearted people who are happy to see her. Like the elderly Madame and her equally elderly housekeeper Barsa, who is really more of a friend than a servant.

Sometimes her clients treat her as a nuisance, like Madame’s rather spoiled granddaughter. Tombo continues to try to win her heart. Kiki goes from completely disinterested to just acting like she’s disinterested because she wants Tombo to try just a little harder.

Tombo feels like a Miyazaki insert. He is obsessed with flight and he also comes across as a thirteen-year-old version of Kiki’s own father. The attraction is understandable. Although, Kiki has to play hard-to-get because those were the rules back then.

Sidenote for men who don’t understand why women used to do this: Think of it as a job interview. If you’re interviewing a candidate, you know that the only reason he’s there is that he wants money and is willing to do what you want in order for you to give him that money. But if he actually said that, you wouldn’t hire him. You expect him to bullshit you in order to get that job and it is the quality of his bullshit that will determine whether or not you hire him. It’s the same thing with girls.

Kiki and Tombo are watching the clouds together while he blathers on about flying. Some of his friends drop by, and they are going to tour an airship together. Tombo invites Kiki along and she stomps off home because “I’m not mad.”

He doesn’t have a clue why Kiki is mad and neither does Kiki. Been there Tombo, we all have.

But this is an important part of her story. She enters a state of depression and loses her ability to fly and worse, she can no longer speak with her cat Jiji. Jiji was her closest friend and ally but now he just wants to hang out with a lady cat of friendly persuasion. Nobody at Ghibli, including Miyazki himself quite knows why Jiji stopped speaking.

Regardless his not being able to fly was a crisis for Kiki. In the book, it’s stated early on that the witches have been losing their powers with each generation. Kiki’s mother could only fly and make potions. Kiki herself could only fly and now she’s lost even that. Can she be called a witch at this point or is she just a girl in a black dress? The witches believe that their power comes from silence and darkness, the modern world Kiki lives in is losing those things, much like our own.

As for Jiji in the book, it is explained that when a baby witch first learns to speak she is paired with a black kitten. They create their own language but when the girl is no longer a child she and the cat will part ways. The symbolism is fairly obvious.

Eventually, kiki sits down with another friend of hers who is an artist and they talk about her problems.

“Flying used to be fun until I started doing it for a living.”

“Do what you love and you’ll never work a day in your life.” Yeah, that’s bullshit, if you are doing it for a living it’s your job. If my accountant tells me I can't be an accountant today, I’m not feeling inspired, then I’m getting a new accountant. The same has to go for working artists, which doesn’t change the fact that we all have to face creative droughts.

This is more Miyazaki’s personal interpretation. The truth is he didn’t particularly want to make this movie. Sure his studio acquired the rights, but it was supposed to be handled as a side project by one of his leading apprentices. For a whole bunch of reasons the project ended up in his lap and he was pretty unhappy about it. Which explains the melancholy tone of the movie that is completely absent in the book. The book is quite bright and hopeful, reflecting the first bloom of youth. The movie is not.

Something that sets Miyazki apart from other Japanese filmmakers is that his stories have an identifiable climax. In Kiki’s Delivery Service, the airship, symbolizing modernity, has an accident that leaves Tombo holding onto one guide rope for dear life. If he slips he will plummet to his death, Kiki regains her passion for life and saves her boyfriend. This makes her the hero of the city and the movie ends with her having regained her passion and thus her ability to fly.

Disney made a rather unwanted change at the end. They gave Jiji a line after Tombo’s rescue, indicating that they could communicate again. This didn’t happen in the Japanese version. I should point out that in the book, Jiji didn’t stop speaking at all, although it was stated explicitly that past a certain point, the young witch and her black cat always go their separate ways. That happened in one of the later Kiki books but I don’t know which one.

It was only one of several changes that nearly had Eiko Kadono killing the project in pre-production. It has taken her a long time to come to grips with it but she now views Studio Ghibli’s film as a masterwork in its own right even though it doesn’t represent her own work.

Kiki’s Delivery Service is one of those films that plays well outside of Japan, but a non-Japanese is never really going to get it on an emotional level. It’s like My Neighbor Totoro in that regard and like Totoro, it addresses similar themes that matter a lot in the Land of Sun Origin.

Tradition versus modernity is very much an issue for a country that was effectively a medieval kingdom at the same time as the American Civil War was going on. When Kiki moves to the city of Koriko, she is initially seen as an outsider, highlighting the Japanese concept of uchi(inside) and soto (outside), and the challenges of integrating traditional values into a modern, urban society

Another layer of meaning is the film’s subtle emphasis on generosity, hospitality, and reciprocal relationships—values which are deeply ingrained in Japanese society. Kiki first survives and then thrives through acts of giving and receiving. First, from the gifts of her parents, then the hospitality of the bakery owner Osono and her husband. Her delivery service is a conduit for connecting people and building community, echoing the Japanese appreciation of mutual support and its tradition of reciprocal gift-giving.

In summary: Kiki’s Delivery Service remains cherished in Japan not only as a beloved animated film but as a thoughtful meditation on growing up, the importance of tradition, versus the challenges of the modern world and Japan’s need to find a place in it.

The fact that the movie is more popular today than when it was released speaks to its ability to address experiences that all humans go through while remaining deeply rooted in Japanese cultural values.

Discuss in the Comments Below

In any discussion of what is the "best" movie, the answer is a Hayao Miazaki film. Which one? It depends.

A bit like during the Campaign to End Puppy-related Sadness, the answer to "What is the best short SF story of the year" the answer was "something by John C. Wright.

Lovely review.

Great article. I watched this more than a few times with my daughter over the years. It's one of her (many!) favourite Miyazaki films.