It’s kind of astonishing when you think about it. One of the most hyper-violent comic book characters of all time started life when the Comic Book Code was still being rigidly enforced.

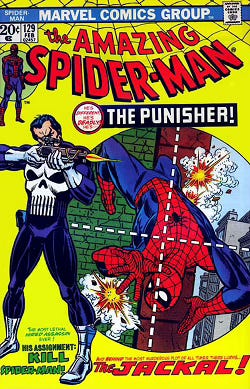

The Punisher first appeared on the cover of Spider-Man 129 in 1974. This was back when Peter Parker had only been around for twelve years himself, and his other half was still viewed as a criminal (thanks, Jonah), which is why Spidey came to the Punisher’s negative attention in the first place.

Frank Castle has been with us for so long that most people have forgotten about the world that called him into being.

By 1974, the Kitty Genovese Murder had been on people’s minds for a decade. City streets weren’t safe to walk at night. Judges seemed to be releasing murderers every day because some bit of evidence was tagged wrong. Police had gone from crime fighters to crime managers, and they weren’t even good at that. And the Baby Boomers appeared to consist entirely of thieving, drug-addled perverts. It felt like the world was out of control, and criminals were no longer being punished. By the book TV cops like Joe Friday weren’t up to the job anymore.

1974 was (not coincidentally) the year that Death Wish came out. Dirty Harry had already been blowing urban monsters away for a couple of years. There were other ‘we’ve had enough movies like: The Last House on the Left, The Outfit, Walking Tall, plus a bunch of B-films I can’t be bothered to look up. This genre didn’t appear in a vacuum; a public that hungered and thirsted for justice wanted to be filled. This was when the modern iteration of the vigilante arrived. It was in this environment that the Punisher was born.

Even if he was going to be problematic for the Comic Book Code

Marvel wasn’t just the House of Ideas because of their characters, they were brilliant at coming up with ways to get around the Code. For example, the CBC had only been around for seventeen years when Morbius was invented for Spider-Man. Morbius was a living vampire, meaning he wasn’t undead, meaning he was (just barely) Code compliant.

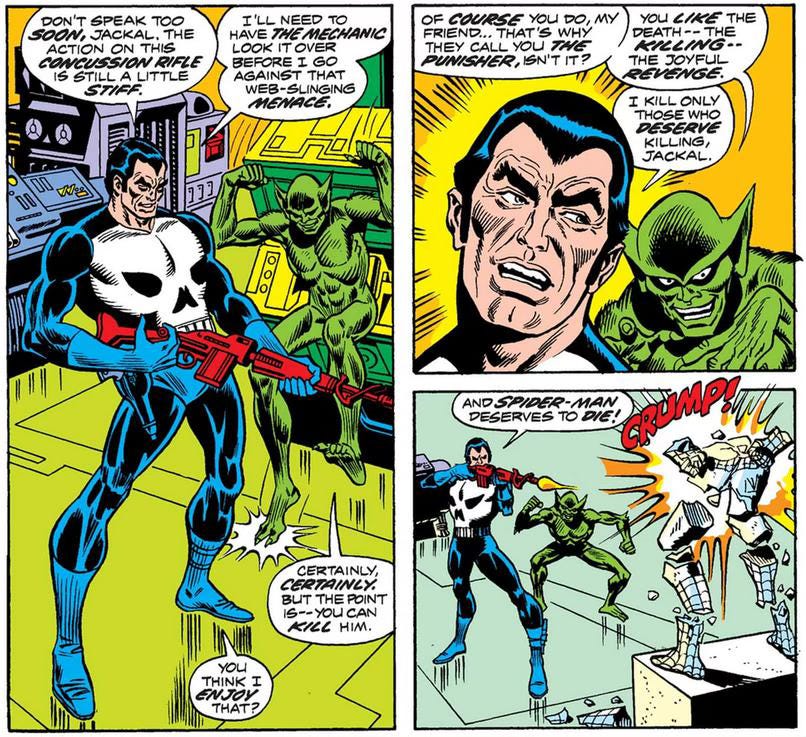

Likewise, the Punisher was framed as a villain. It was perfectly fine for a villain to kill criminals since he was a bad guy. He was NOT being glorified, no matter how much his readers liked what he was doing. That made him Code legal.

Marvel reinforced this by leaning hard into presenting him as seeking justice for his murdered family. He was not, at first, just mindlessly blasting every criminal he came across. This made Frank Castle a tragic villain, driven by trauma. Being driven by trauma was pretty standard comic book villain stuff. The CBC wasn’t in a position to start objecting to that after 20 years.

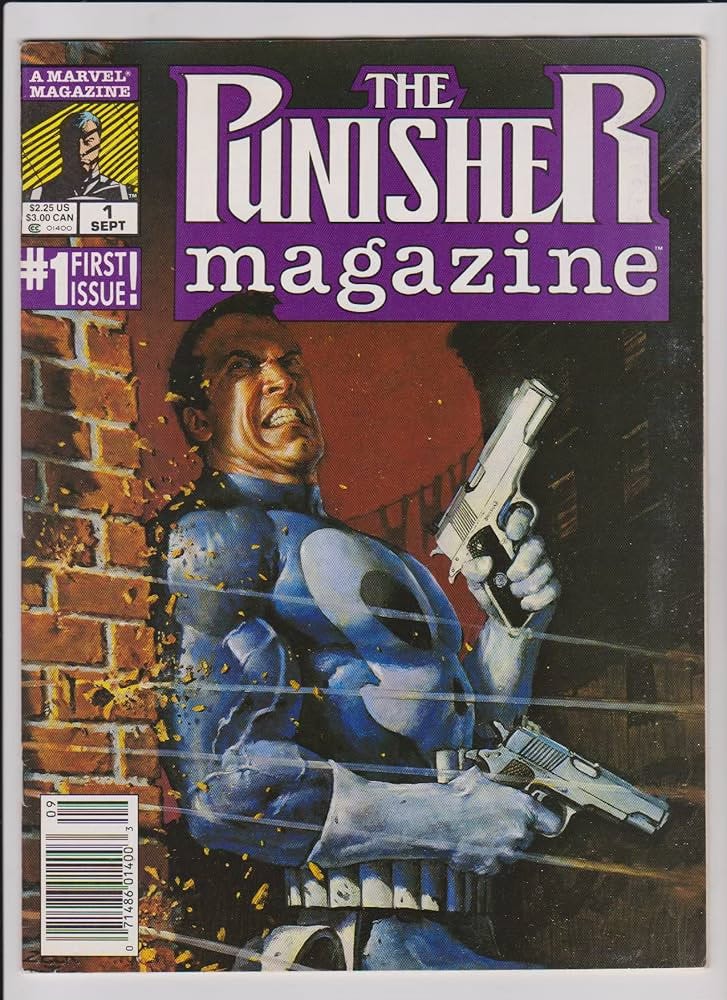

Marvel at this time had a ‘magazine’ titled The Savage Sword of Conan. Since it was in black and white and had ‘magazine’ in the name, the Code could go play with itself. Kids weren’t supposed to be able to buy it anyway, and in the seventies, finding a shop owner who didn’t care about that could be tougher than you’d think.

Since the Punisher was basically Conan with a gun, he rated his own black and white ‘magazine,’ where the Punisher became violently graphic.

That said, the violence had to be toned way down if he were in color. His guns would fire, but no one seemed to get hurt all that much. I know it sounds silly, but this was also the period where the A-Team was routinely burning up hundreds of rounds per episode and killing exactly ZERO bad guys.

The Indie comics scene in the eighties began applying a great deal of pressure to the Code authority to ease up, and they complied. It wasn’t like they were a government agency; it was something the comic book publishers came up with to appease mothers in the 1950s. And Fredric Wertham had died in 1981.

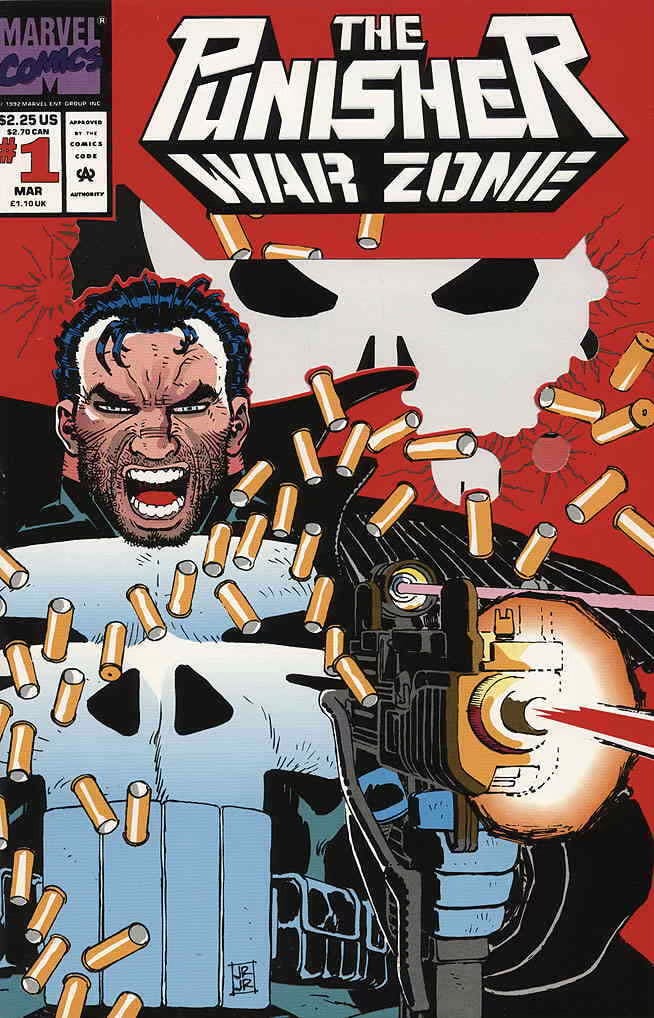

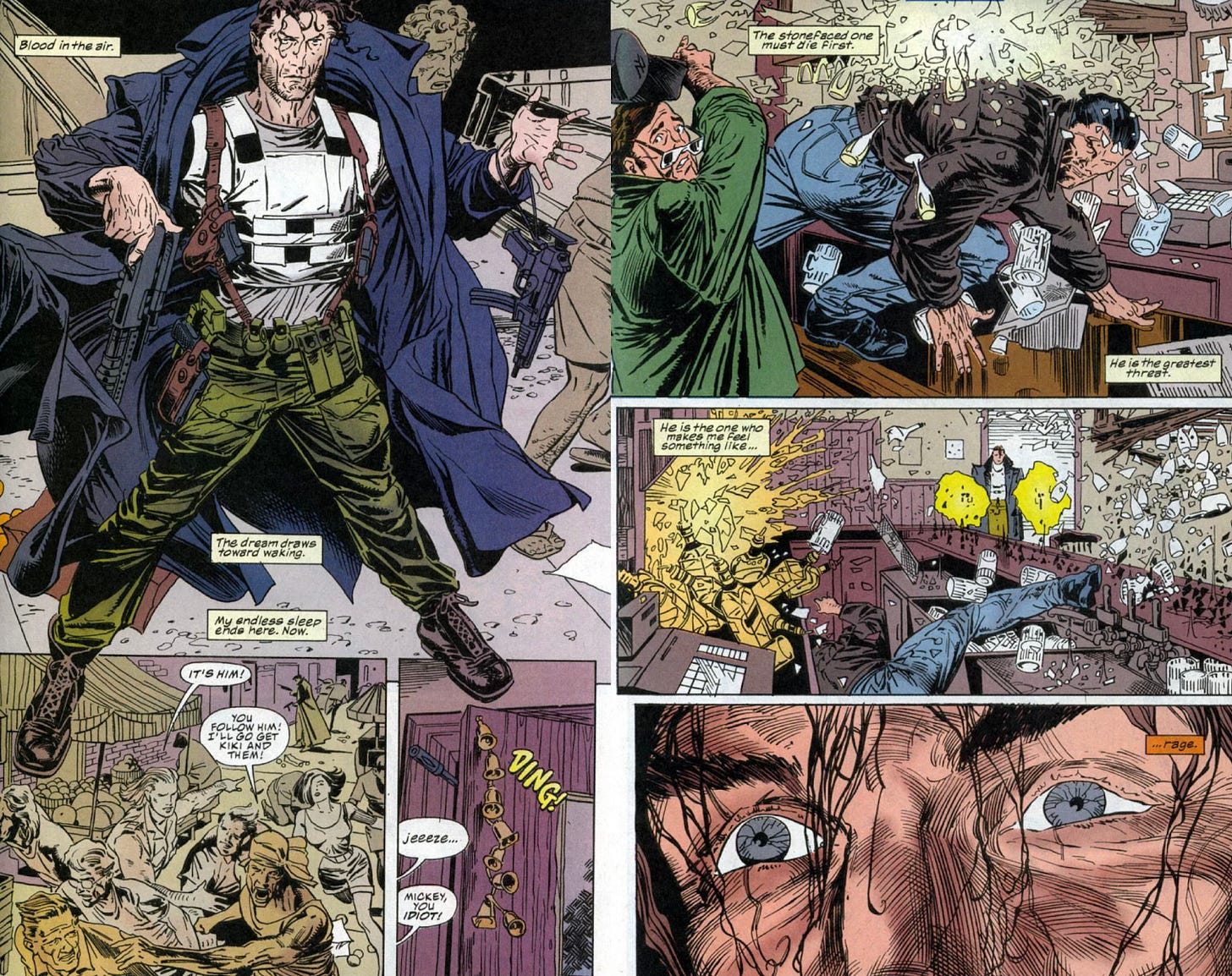

When the 1990s came around, it was time to show what the Punisher was capable of in glorious ultra-violent color. John Romita Jr. would be doing the pencils, but it was going to need a writer who could deliver a Frank Castle at his most hard-hitting, ruthless. Chuck Dixon began a run with the Punisher that would be, in a word, legendary.

Today, we’ll be taking a look at Chuck’s work on The Punisher War Zone.

By the early 1990s, the Punisher was at the zenith of his popularity. Generation X by now had made’s tastes very well known. We knew something had gone wrong after the world woke up from history. We couldn’t put our finger on what was wrong just yet, but we knew somehow and in some way we had been cheated, and we were mad as hell about it.

The Punisher spoke to us in a way that he hadn’t for the Boomers. He didn’t speak to our insecurity about urban life but to our anger.

During the 1980s, the Punisher had leaned a little too much into the crazed Vietnam veteran cliches. Dixon’s Punisher was a much purer avatar of fury, but he didn’t discard Frank Castle’s military background; if anything, he used it as a much stronger foundation for the Punisher’s planning and tactics. It made him more grounded. More gritty.

There’s an old saying in military circles: in a crisis, you revert to the level of your training. A famous example of that is a pair of Chicago cops that were killed in a gunfight because they were collecting spent brass just like they’d been trained to do. Castle was writing himself five-paragraph orders before hunting members of the Carbone family.

The eighties Punisher was occasionally given to moaning about his internal moral quandaries and whinging about his justification before getting on with the business of killing the baddies of New York City. Dixon’s Punisher was focused on a military man’s first function and primary obligation, the completion of his mission.

Or at least that’s how Dixon’s Frank Castle started life. However, and this was the big thing Chuck Dixon brought to the party, somewhere along the way, Frank Castle was consumed, his murdered family became disconnected from him as he accepted the truth that Frank had died with the rest of his family and that now he was only The Punisher. What little moral ambiguity he had been harboring had been cut loose and allowed to sink. There was no dream of finding a normal life, there was no seeking redemption or absolution for his acts. He would do everything he had done again. He was not a madman; he was the only sane man in an insane world, and he knew it.

It stripped away his humanity and made him more of an unchanging archetype. The Punisher, while still grounded, began his journey to become a near-mythic avatar of justice when justice had failed.

Dixon’s iteration of character completely discards Baron’s absurdist, off-beat, and sometimes even humorous takes. However, Dixon’s Punisher, while dark, stopped at the door of Ennis’s completely nihilist hollow man framing of the character. Dixon’s character still knew the meaning of mercy and compassion, even if he didn’t have any, not for criminals that had rejected their humanity or, in the final analysis, for himself. His story would never be one of redemption.

Dixon leaned into the title heavily as a framing device. The Punisher was now at war. My favorite story arc was still the opening one, The Sicilian Saga, where the Punisher infiltrates the mafia to gain intelligence about its operations, targets them, and then destroys them utterly. While there were some interesting side characters like Shotgun and Microchip but my favorite Dixon character was the half-dead Thorne. Thorne had been Sal Carbone, an enforcer for the family, but after The Punisher shot Sal and left him under the ice, he emerged as the amnesiac flesh-golem Thorne.

I can’t talk about War Zone without mentioning John Romita Jr. His bold and dynamic line work as well as his detailed (if rarely pretty) faces was a perfect match for the Legend’s storytelling. His artwork was unmistakably hard edged, and kinetic. Exactly what was needed for a comic book with War Zone right in the title.

The critical reception was on the mixed side, or so I’m told, finding bad reviews for this was defying the minimal efforts needed to find anything of note or consequence. The fans loved it. It was a huge seller for Marvel and has now become the kind of gold-dust title that is eagerly sought.

Chuck Dixon’s War Zone is the title that defines the Punisher that most know him by today. It’s Dixon’s iteration of the character that has created his untenable popularity today.

Which is a huge problem for Marvel. Or to be more exact, Disney/Marvel.

It is a supreme irony that the company that now owns him is deeply embarrassed by him. Everything he stands for is loathed by every level of current-year Marvel. His iconic logo infuriates Disney/Marvel’s entire corporate culture. This has led to an internal conflict at the company.

On the one hand, they are revolted by the values it has come to represent to American fighting men. They hate it with every fiber of their existence.

On the other hand, if they don’t make money off it, they will lose the control of it due to common use. Losing IP goes against the fundamental DNA of the company. They humiliated and destroyed the Punisher in one of their recent and completely unread comics.

And doesn’t matter in the least. It was ultimately a measure of their own impotence, their complete inability to control the uncontrollable creation of The Legend Chuck Dixon.

Discuss in comments below

Loved this article. Thanks! The fingers on the triggers comment was gold!

Man, I miss the days when Marvel actually made good comics.